A couple years ago I started a day job as a part time school librarian. There is an intersection of adoption and children’s books more often than you might think. The school library I am caretaker for contains books from quite a few decades. You can see the changing racial attitudes mirrored in the books produced at the time. Picture books have come a long way in their inclusivity. “Representation Matters” is a frequent slogan to underscore the idea that children need to read books which show children like themselves. However, publishing houses still have unconscious biases and blind spots. It would be easier to find the Fountain of Youth than to find a picture book which shows anyone anywhere in the massive continent of Africa living in a city. I mean, there are 13 million people living in Lagos, Nigeria (shown below) which is more than 4 times the population of my home state of Kentucky, but it’s grass huts as far as the eye can see in picture books.

A similar blind spot exists where Asians and Christmas are concerned. While publishers have finally realized Christmas is celebrated by more than just white people and talking animals, the many diverse Christmas pictures books published with the past decade haven’t yet grown to include Asians. In December, someone asked online for suggestions of Christmas picture books featuring Asians. The response was a collective shrug. “Christmas isn’t really an Asian thing.” was a typical reply. It is unclear if that referred to Asian as in the region of the world or to an ethnic minority here in the US. Presumably since we’re discussing Christmas picture books in English for American children the implication is that Asians here in America completely ignore Christmas in favor of the lunar New Year. The problem with that is it isn’t true. There are people here in America whose ancestors immigrated from China in the late 1800’s. Even the relatively “new” wave of immigrants from the 1970’s or later participate in American cultural holidays. When I lived in graduate student housing international students from across Asia bought small Christmas trees to decorate in their apartments because it was fun. Now I live in a suburb and I see Asian American families putting up lights the same as the European American families.

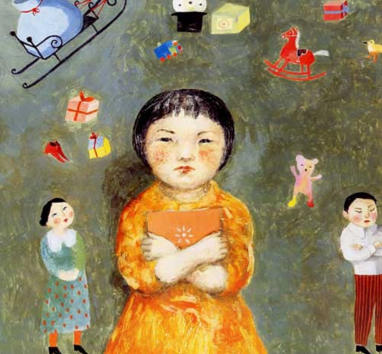

The one book which several people suggested was Yoon and the Christmas Mitten. This is a sequel to the book My Name is Yoon by Helen Recorvits which won several awards when it was published in 2003. My Name Is Yoon is about a Korean family who immigrates to America. Yoon is reluctant to write her name in English at school because she prefers the way it looks in Korean. In the end, her father urges her to learn to write in English because they are American now. I found it to be positive and respectful. However, Yoon and the Christmas Mitten is almost the situation in reverse as Yoon learns about Christmas at school and begs her parents to celebrate the holiday. Her parents say “Little Yoon, we aren’t a Christmas family. Our holiday is New Year’s Day.” After Yoon reminds them that they are supposed to be American now, they put some candy in the mitten she has hung on Christmas Eve.

The one book which several people suggested was Yoon and the Christmas Mitten. This is a sequel to the book My Name is Yoon by Helen Recorvits which won several awards when it was published in 2003. My Name Is Yoon is about a Korean family who immigrates to America. Yoon is reluctant to write her name in English at school because she prefers the way it looks in Korean. In the end, her father urges her to learn to write in English because they are American now. I found it to be positive and respectful. However, Yoon and the Christmas Mitten is almost the situation in reverse as Yoon learns about Christmas at school and begs her parents to celebrate the holiday. Her parents say “Little Yoon, we aren’t a Christmas family. Our holiday is New Year’s Day.” After Yoon reminds them that they are supposed to be American now, they put some candy in the mitten she has hung on Christmas Eve.

There is a huge glaring plot hole here which the average American wouldn’t catch. Of all the East Asian countries Recorvits could have chosen, Korea is the worst choice for the book she wrote. Korea has a very long history of Christianity. Today Korea is about one third Christian, a far larger percentage than any other East Asian country. Christmas is a national holiday in Korea! It has been since 1945. Although the time frame of the book is unclear, Yoon’s family should have at least been familiar with Christmas. When Yoon tells her father about Santa Claus, he says “We are Korean. Santa Claus is not our custom.” But, in reality Korea has their own version of Santa Claus.

Consider how different the message of the story would be if Yoon’s family were new immigrants who joined a Korean Christian church in their community. When Christmas rolled around, the familiarity of the holiday gives Yoon’s family a feeling of connection and belonging to their new country. When Yoon’s teacher reads the class a book about Santa Claus, Yoon shares with the class that they have Santa Claus in Korea, too. Instead of decorating “Christmas bushes” with bread crumbs, Yoon could decorate a Christmas tree with her family the same way they did in Korea.

Consider how different the message of the story would be if Yoon’s family were new immigrants who joined a Korean Christian church in their community. When Christmas rolled around, the familiarity of the holiday gives Yoon’s family a feeling of connection and belonging to their new country. When Yoon’s teacher reads the class a book about Santa Claus, Yoon shares with the class that they have Santa Claus in Korea, too. Instead of decorating “Christmas bushes” with bread crumbs, Yoon could decorate a Christmas tree with her family the same way they did in Korea.

As it is written Yoon and the Christmas Mitten reinforces the idea that Asians are perpetual foreigners in America. We can’t imagine an America where Asians are decorating trees, putting up lights, and making Christmas cookies. The only way we can put Asians and Christmas together is a book where “real” Americans explain to the Asian family what Christmas is. Yoon must persuade her family to cast aside their foreign skepticism of Christmas if they want to try to assimilate. An Asian child who reads this book would only see themselves represented as an outsider. Yes, it is important that you share books with Asian characters with your child so they see themselves represented. However, it isn’t enough to simply have an Asian character. Please carefully consider the message of the book whether it is a “classic” like Tikki Tikki Tembo or a newer book like The Ugly Dumpling which portrays Chinese food as ugly and Chinese restaurants as unsanitary. The two articles I linked to in this paragraph will help you to gain perspective on potentially problematic elements in stories.

The one book which several people suggested was Yoon and the Christmas Mitten. This is a sequel to the book My Name is Yoon by Helen Recorvits which won several awards when it was published in 2003. My Name Is Yoon is about a Korean family who immigrates to America. Yoon is reluctant to write her name in English at school because she prefers the way it looks in Korean. In the end, her father urges her to learn to write in English because they are American now. I found it to be positive and respectful. However, Yoon and the Christmas Mitten is almost the situation in reverse as Yoon learns about Christmas at school and begs her parents to celebrate the holiday. Her parents say “Little Yoon, we aren’t a Christmas family. Our holiday is New Year’s Day.” After Yoon reminds them that they are supposed to be American now, they put some candy in the mitten she has hung on Christmas Eve.

The one book which several people suggested was Yoon and the Christmas Mitten. This is a sequel to the book My Name is Yoon by Helen Recorvits which won several awards when it was published in 2003. My Name Is Yoon is about a Korean family who immigrates to America. Yoon is reluctant to write her name in English at school because she prefers the way it looks in Korean. In the end, her father urges her to learn to write in English because they are American now. I found it to be positive and respectful. However, Yoon and the Christmas Mitten is almost the situation in reverse as Yoon learns about Christmas at school and begs her parents to celebrate the holiday. Her parents say “Little Yoon, we aren’t a Christmas family. Our holiday is New Year’s Day.” After Yoon reminds them that they are supposed to be American now, they put some candy in the mitten she has hung on Christmas Eve.